This site chronicles the history and ongoing restoration of the Dr. Oliver Bronson House & Estate in Hudson, NY; a National Historic Landmark. First built as a Federal style residence for Samuel Plumb in 1812, the house and grounds were reinvented by architect Alexander Jackson Davis into a fully realized early Picturesque landscape for Dr. Bronson and his family in two successive remodeling campaigns dating to 1839 and 1849. Continue reading “Welcome to the Day Book!”

Archeological Discoveries: Marble Curbing

On the third day of the dig, the archeologists found a small section of white marble curbing consisting of three blocks (about 20 inches long by 2.5 inches wide x 10.5 inches tall) underneath a thick slab of concrete (part of the twentieth century basement areaway treatment). The line of curbing ran southward, perpendicular to the house and was continued on to the south with a line of common bricks. It probably served as some type of low retaining wall although subsequent disturbances to the area make it difficult to interpret. The granular white marble used for the curbing is, according to the archeology report, consistent with the widely quarried in Westchester County during the second quarter of the nineteenth century. The report also notes that Samuel Plumb’s brother David Plumb advertised in the Northern Whig as early as 1814 that he had marble slabs for sale. So, it is possible that this curbing was part of the original Plumb-era landscape treatment or was perhaps re-used in a later campaign. Perhaps we will find some additional sections of curbing in the follow-on archeological study which can add to the story here.

Archeological Discoveries: Cobblestone Paving

So, after the long period of suspense (and silence from this blog writer), you are probably asking yourself what exactly did the Hartgen team find? Well, lots of stuff… Which, in turn, answered some questions and raised many more.

Perhaps the most dramatic find was a very well-preserved section of historic cobblestone paving about a foot below the surface of the turf. The Hartgen team tenatively dated this feature to 1850s-60s (Folger ownership) based on physical evidence (whiteware ceramic sherds) and other historic residential examples in the Hudson area dating to the same period (many of the City of Hudson’s streets were also paved with cobblestone in the 1860s).

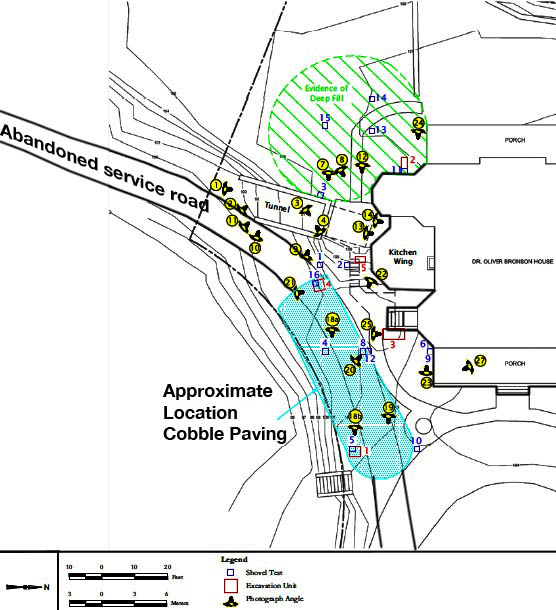

To uncover the extent of the cobblestone feature, the archeologists systematically dug a series of test pits at regular intervals in the surrounding area. The cobblestone drive/yard turned out to be pretty large, approximately forty foot long by fourteen feet wide. The area shown in light blue in the diagram below show the approximate location of the find:

According to the archeologists, the presence of layers of ash and cinders on top of this paving suggests that it had been exposed to the elements for many years and then perhaps abandoned and covered over in the early twentieth century during the period of state ownership (1915-1975).

The cobblestone paving appears to have been part of a larger service drive system which was altered multiple times over the years. An early twentieth century photo of the east elevation of the house provides some tantalizing (and blurry) visual evidence of at least what one incarnation of what this design looked like. The area of cobblestone paving discovered by the archeologists begins just where the (packed gravel?) drive in the foreground of the photo dips down and continues along the south side of the house (left side of the photo) before connecting to the now abandoned service road running out to the southwest. I’ve squinted at this photo for a while but still cannot see anything definitive.

The area in the foreground of the historic photo is now covered over with an asphalt carriage loop, and, closer to the house, a concrete sidewalk poured in the 1950s. So more evidence may exist underneath these modern layers. The photo below shows the site conditions of the same area at the conclusion of the archeological work. As you can see, the modern grade is much more gentle than the historic photo reflecting multiple regrading campaigns during the early twentieth century.

The rectangular areas closed off with yellow tape and stones in the photo above mark two of the test pits in which cobble paving were found. These were covered over with plywood to allow re-inspection in the future.

One thing that does seem clear from the archeological study is that only a portion of the service drive was ever paved with cobbles. The archeologists discovered a clean edge south west of the house where the cobblestone paving transitions to the cinder road base of the service road.

This suggests that the more expensive cobblestone paving was used near the house as both a decorative and functional element. The sloping grade and clay soils on the south side of the house make it as muddy today as it was in the past. The cobblestones paving provided an all-weather hard surface in the heaviest use areas which could support horses and wagons bringing food and supplies to the adjoining kitchen/service areas. How exactly the paving connected to these service areas during different historical epoch is still very unclear and will be the subject of additional archeological work in the Spring/Summer of 2013.

Digging in the Dirt – Part I

At the end of August, Matt Kirk (pictured above) led a team from Hartgen Archeology (www.hartgen.com ) on a four-day landscape/architectural investigation on the south side of the house. Following standard practice, an archeological grid was laid out around the house and existing landscape features were mapped on to it to provide a context for the analysis. Next, a series of sixteen test pit locations were identified in conjunction with the archeologists and our architects to help guide the study. The diagram below shows the preliminary test pit locations:

At the end of August, Matt Kirk (pictured above) led a team from Hartgen Archeology (www.hartgen.com ) on a four-day landscape/architectural investigation on the south side of the house. Following standard practice, an archeological grid was laid out around the house and existing landscape features were mapped on to it to provide a context for the analysis. Next, a series of sixteen test pit locations were identified in conjunction with the archeologists and our architects to help guide the study. The diagram below shows the preliminary test pit locations:

Each of these so-called “shovel tests” were dug to understand the stratigraphy of the soil (including the location and depth of builder’s trenches), uncover artifacts (hopefully dateable), and reveal earlier landscape features (drives, paths, retaining walls, etc). In addition, the project called for the removal of the concrete cap and partially collapsed vault of the brick tunnel so that the area closer to the foundation could be safely investigated (we didn’t want any casualties here).

And away we went…

Phase II Ramps Up

What with all the posts about movies and photos shots you are probably thinking we are not doing any work around here. But rest assured, we have been working hard on planning the next phase of the restoration.

The first step was to obtain the base funding to pursue the project. In the Fall of 2010, we were awarded a $58,500 New York State Environmental Plan Fund (EPF) grant allowing us to develop a detailed plan for the restoration including the creation of architectural drawings, bid documents, engineering studies, and archaeology reports. In the Fall of 2011, we were awarded a second EPF grant of $300,000 to conduct the Phase II restoration itself. The EPF grants requires us to raise matching funds from private sources including foundations, individual donors, and, yes, movies and photo shoots. Currently, we still need to raise $125,000 to begin the construction in Spring/Summer 2013.

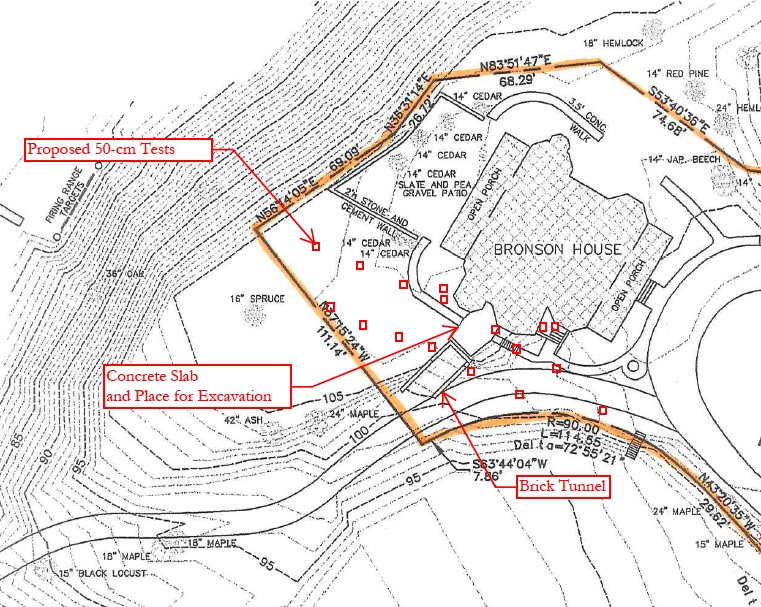

Phase II of the restoration will concentrate on stabilizing the south side of the house including rebuilding partially collapsed stone foundations, restoring the southwest Davis bay from 1849, and completing the rest of the roof replacement. All of this sounds relatively straightforward until one see the actual site conditions:

The south elevation presents a daunting jumble of later service additions and accretions as well as erratic grade changes. Included in this is a highly dilapidated one-story kitchen addition on a brick foundation, a brick tunnel of unknown function with later concrete retaining walls and ramp, and a partially collapsed flag stone and concrete patio.

All of this presents real challenges for preservation and restoration work (not to mention substantial health and safety issues). One cannot attempt to rebuild the stone foundations of the original house without removing some or all of the later accretions built in front of and over them. But before you start bringing in heavy equipment to remove any material you first need to understand the historical layers that you have and the pattern of building and landscape evolution. When was the kitchen addition added? What was the brick tunnel used for? What did the historical grade look like? There is a lot of important information hidden here that we need to understand before we move forward.

Our primary historical period of significance for the restoration is the residency of Oliver Bronson and family (1838-1854). Landscape was an integral part of A.J. Davis’s design work and we are particularly interested in learning more about the historical grading, path systems, fencing and retaining walls that were part of Davis’s 1839 composition and the changes he made when he returned in 1849 to create the large new tower addition.

Accordingly, as part of planning for Phase II, we are devoting substantial resources to archaeological investigations, and site plan work to learn as much as we can about the Davis-era appearance of the house and landscape before beginning any active restoration work. This work will inform the preparation of the final architectural drawing and construction documents by our architects Mesick-Cohen-Wilson-Baker Architects (www.mcwb-arch.com). We have selected Hartgen Archaeological Associates (www.hartgen.com) of Rensselaer, New York to work with us and our architects in investigating the area around the south side of the house. Hartgen brings extensive archaeological experience working on historical sites in New York state and beyond to the project team. Additionally, we have retained the landscape architect firm Robert M. Toole & Associates of Saratoga Springs, New York to update the historical landscape study prepared for us in 2000.

Anthropologie Photo Shoot

File this post under more stuff we have been keeping a lid on…

Back at the end of June, über-hip clothing and housewares retailer Anthropologie shot a portion of its September catalog at the Dr. Oliver Bronson House. Good for us and good for them. It was an extremely hot day, and the Philadelphia and New York-based crew sweltered as they as they carried furniture up and down the stairs (yes, I was watching to make sure nothing happened to the house) and carefully composed each shot. But true professionals that they are, the Anthropologie team maintained their cool in the heat and achieved some impressive artistic results.

Now that the September catalog is finally out, I wanted to share some images from the shoot:

No more plywood

In the Bourne Legacy movie (www.thebournelegacy.com), this wall is covered in plywood. But soon after the Universal crew left in early November, Jesse Tuttle and company finished the reinstallation of the restored original six-over-six window sash into the north wall of the study. So I wanted to show it to you and also prove that, unlike as shown in the movie, we didn’t burn down the house (as an all-volunteer non-profit organization we are eager for contributions to assist the restoration – just not that eager).

In the Bourne Legacy movie (www.thebournelegacy.com), this wall is covered in plywood. But soon after the Universal crew left in early November, Jesse Tuttle and company finished the reinstallation of the restored original six-over-six window sash into the north wall of the study. So I wanted to show it to you and also prove that, unlike as shown in the movie, we didn’t burn down the house (as an all-volunteer non-profit organization we are eager for contributions to assist the restoration – just not that eager).

Next Spring, we hope to remove the rest of the plywood on the Federal period bays (to the left of the photo)….

Dr. Oliver Bronson House Stars in a New Movie

We have been keeping a lid on it (to respect the confidentiality of our partners), but now we can talk about it. Last November, Universal Pictures filmed a portion of the Bourne Legacy (the latest in the Bourne movie franchise) at the Dr. Oliver Bronson House. A 150-person crew was on site for eight days, digitally mapping the facade of the house and shooting exterior action sequences. The movie shoot was a boon for the local economy and helped us raise a portion of our Phase II Restoration matching funds.

Universal had originally wanted to film inside the house but Historic Hudson, working in conjunction with our architects (Mesick-Cohen-Wilson-Baker-Architects), and outside structural engineers, determined that this posed too much risk to the fragile historic structure and its interiors. Instead, Universal recreated the entire house interior (down to the peeling wallpaper) at the Kaufman Astoria Soundstage in Queens. Below is a shot of the north side of the building the weekend before the shoot and its appearance in a recent trailer for the movie. Note the beautiful plywood covering the north-west room of the original Federal period house in both shots. More photos from the movie shoot will be posted on Historic Hudson’s Facebook page over the next couple of days. The Bourne Legacy opens in theaters nationwide this Friday (August 10).

Heritage Weekend 2012

On the weekend of May 19-20, Historic Hudson participated in NY Heritage weekend http://www.heritageweekend.org Guided tours of the Dr. Oliver Bronson House were offered on both days, highlighting all of the important restoration work completed during Phase I. In all, about 200 people visited the house. I should know, I was one of the tour guides. I met lots of interesting people and did lots of talking.

In addition to seeing the progress of the restoration, many visitors used the opportunity to take photographs. Ghent-based professional photographer Michael Fredericks michaelfredericks.com took this great shot lying on his back in the first floor hall floor using a very wide-angle lens. Everything in the service of his art – Thanks Michael.

Look out below!

Up until early September, you had to be very careful in this room. One false step and you would end up in the basement. But thanks to the efforts of Jesse Tuttle and company, who rebuilt/reinforced the framing below and patched in the flooring, visitors to the house can walk around the room without a trip to the emergency room.

Brothers and sisters

The reason the house is standing taller and the roof planes are cutting cleaner is that there have been a lot of structural repairs underneath the hood. Where possible, Jesse and his team have tried to “sister” onto the existing framing, providing new wood on either side of the two hundred-year-old original timbers (I guess they are some “brothers” in there as well). Below are some examples from the NE Federal Dining Room bay: